Writing in his diary in January 1985, Andy Warhol described a visit to the Park Avenue South loft of Julian Schnabel, one of his primary rivals in art-world notoriety at the time: “Bryan Ferry was there. Julian has all his own art in the place and he tells you about each one, he stands there and reads into his own work. I mean, he literally stands there and…tells you what his paintings mean.”

Julian Schnabel has painted on everything from velvet and burlap to linoleum and, most famously, on broken plates. His usage of unlikely materials with histories, combined with his unconventional methods of application (hoses, spray cans, fingers, paint-soaked cloth), unite the past four decades of his output.

“I’m really interested in the idea of how something is printed, whether it’s by time or stain or actual printing—how you apply an image to a surface,” he said.

Schnabel’s art was characterized by its chaotic profusion of styles and sources.

Schnabel’s gestural application of paint on massive canvases, use of unconventional materials like broken plates, and representation of human figure are hallmarks of his most famous works. “My paintings take up room, they make a stand. People will always react to that,” he said of his work. “Some people get inspired, others get offended. But, that’s good. I like that.”

Julian Schnabel as film director

Julian Schnabel began his film career in the 1990s with the film Basquiat, a biopic on his friend and painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, followed by Before Night Falls (2000), an adaptation of Reinaldo Arenas’ autobiographical novel, which he also produced. He directed The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007), an adaptation (with a screenplay by Ronald Harwood) of a French memoir by Jean-Dominique Bauby.

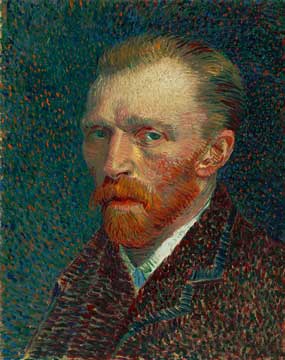

In 2007, Julian Schnabel designed Lou Reed’s critically acclaimed “Berlin” Tour and released Lou Reed’s Berlin. In 2010, Schnabel then directed the film Miral (see further). The film At Eternity’s Gate, about the painter Vincent Van Gogh during his time in Arles and Auvers-sur-Oise, was released in 2018.

At Eternity’s Gate

As director of the film “At Eternity’s Gate” Julian Schnabel wants us to understand – experience – how the great Vincent van Gogh looked at the world, and how he translated his experience into brushstrokes.

The film focuses on Van Gogh’s last, most insane years in the South of France, but Schnabel refuses to portray Van Gogh merely as a self-destructive fool. On the contrary: when he stands with his arms in the air watching the sunset on one of his long nature walks, he seems more deeply happy than desperate. For when he stares over the fields, he says, he sees nothing but eternity. No matter how unstable his life was, he experienced it at least more intensely than the average mortal.

At Eternity’s Gate is not a traditional biopic, nor is it a purely experimental affair. Schnabel lands somewhere in the middle, and that’s actually fine. The impressionistic camera work stimulates the senses, and sometimes the director experiments with style effects that are meant to represent Van Gogh’s state of mind. In this way you never get the feeling that you are looking at a moving painting but that you are in his shoes.

At Eternity’s Gate: a fascinating fusion of a trio of artists

Subject Vincent Van Gogh, performer Willem Dafoe, and filmmaker Julian Schnabel. Far less concerned with traditional biopic beats that seek to hit the high points of a famous life, the director delivers a film more interested in philosophy and process than product. And rarely has a film been more of a singular showcase for a performer.

biopic beats that seek to hit the high points of a famous life, the director delivers a film more interested in philosophy and process than product. And rarely has a film been more of a singular showcase for a performer.

Schnabel’s camera is often moving and often in close-up, as if the filmmaker is trying to find the magic in Dafoe’s performance in the same way that Van Gogh tried to find the magic in a landscape he was painting.

It’s an impressionistic film, concerned more with the atmosphere around genius than explaining it away.

In one of the film’s best scenes, Van Gogh tells a priest (Mads Mikkelsen) sent to judge his sanity that he believes perhaps God made him “a painter for people who weren’t born yet.”

Did Van Gogh really have this much of an understanding of how rarely great art is appreciated in the great artist’s lifetime? Art historians can debate that more accurately than myself, but it’s an underlying theme of Schnabel’s take on a man too often reduced to the story of his ear. Schnabel paints Vincent Van Gogh as something of an anomaly in his own time, an outsider to the entire world almost because he could see it differently than anybody else.

Miral: the Arab-Israeli conflict through the eyes of four Palestinian women

In Miral (2010) Schnabel explored the Arab-Israeli conflict through the eyes of four Palestinian women living in Israel in the mid-to-late 20th century.

Jerusalem, 1948. On her way to work, Hind Husseini runs into 55 street children. She takes the orphans to her house and gives them food and drink. Within six months the number of orphans has risen from 55 to almost 2000 and the ‘Dar Al-Tifel’ institute is born. Miral (Freida Pinto) is sent to the institute by her father at the age of 7. Safely raised in the orphanage and naive as she is, at the age of 17 she is sent to a refugee camp, where she has to function as a teacher. Here, the first naive Miral is confronted with the harsh reality. When she falls for political activist Hani, she soon finds herself between two fires; the future of her loved ones and ‘Mama’ Hind’s belief that (her) education is a road to peace.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been the subject of so many films that it is not easy to come up with an original angle. By looking at the events from the eyes of a number of courageous and involved women, Schnabel has the opportunity to distinguish himself from his colleagues. He has chosen to keep the bloodshed to a minimum and to show the real ‘great events’ in world history by means of archive footage.

“If you ask most people who do have an opinion of the work of Julian Schnabel what they’ve seen recently, or which works they are referring to, they usually say the plate paintings, which basically means these people have not looked at his work for 30 years. It’s always important, especially with work like Julian’s, that you really see it before making your judgements.”